Alicia Nicholls

Caribbean Citizenship by Investment (CBI) programmes, and to a lesser but growing extent, residence by investment (RBI) programmes, are facing a rough ride. The latest blow came when the Paris-based Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) deemed CBI/RBI programmes operated by 21 jurisdictions, including those in the Caribbean, as “high risk to the integrity of the Common Reporting Standard”. While the OECD has clarified that this was not a blacklist, the list puts another glaring spotlight on Caribbean CBI/RBI programmes which are already battling to justify their existence to an increasing choir of skeptics. In October, the European Union (EU) released a report analysing the state of play, issues and impacts of its own members’ programmes. With the mounting scrutiny being placed on Caribbean countries’ CBI/RBI programmes and stiffened competition from other investment migration programmes globally, have Caribbean countries’ CBI programmes run their course?

What are CBI Programmes?

CBI programmes are one of the two main types of investment migration programme – programmes which offer high net worth (HNW) investors accelerated citizenship or residence of the host country in exchange for a pecuniary contribution. Unlike RBI programmes which only confer accelerated permanent residence status, CBI programmes grant a qualifying investor, upon making a specified economic contribution to the host country (usually in real estate, investment in a business or in a specified government fund), accelerated citizenship for himself/herself and his/her qualifying spouse and/or dependents, once all relevant fees are paid and due diligence requirements are met. It means that a person can acquire citizenship or residence of another country in just a few months, compared to several years under regular naturalisation procedures.

Five Caribbean countries currently operate CBI programmes: St. Kitts & Nevis (the world’s oldest CBI programme), Dominica, Grenada, Antigua & Barbuda and St. Lucia. International examples include the EU member states of Austria, Cyprus and Malta, and the Pacific island nation of Vanuatu.

Second citizenship is a booming international industry reportedly worth US $3 billion, according to Citizenship by Investment.ch. There are now over one hundred CBI/RBI programmes worldwide, which seek to lure an expanding and highly mobile class of global High Net Worth Individuals (HNWIs) seeking the advantages a more favourable second passport could bring for themselves and their families. These advantages include greater mobility and security, tax planning advantages, and business opportunities.

The British Overseas Territory of Anguilla is the most recent Caribbean jurisdiction to commence a RBI programme, but versions of these programmes are also operated in the Bahamas, Barbados, Montserrat and Turks & Caicos, for example. Examples of RBI programmes in developed countries include the United States’ EB-5 programme and the United Kingdom’s Tier 1 Visa.

Challenges to Caribbean CBI/RBI programmes

Those Caribbean countries which operate them view these programmes as a pathway for economic diversification and development, bringing greatly needed foreign exchange and foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, infrastructure development, and employment opportunities. In its Article IV Report on Dominica, which had been badly affected by category five Hurricane Maria in September 2017, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) noted that “fiscal performance deteriorated sharply due to the fall in tax revenue after the hurricane, but was partially offset by a surge in grants and buoyant Citizenship-by-Investment (CBI) sales revenues.”

Despite their economic benefits, CBI programmes have always been controversial due to some governments’ philosophical aversion to what many have called the “commodification of citizenship” or “selling of passports”. Indeed, CARICOM Member States remain philosophically divided on the desirability of CBI programmes.

There have also been, in some cases, legitimate concerns about the efficacy of the due diligence procedures, the perceived absence of a ‘genuine link’ between recipients of citizenship under CBI programmes and the host country, and reports of alleged instances of misuse of passports obtained under CBI programmes, which have brought increased international scrutiny of Caribbean countries’ CBI programmes.

One of the pull factors of Caribbean countries’ CBI programmes is the visa free access. For example, on the Henley & Partners Passport Index published by the world’s leading investment migration firm, Henley & Partners, St. Kitts and Nevis ranked the highest among Caribbean CBI countries in the strength of its passport, providing visa-free access to 151 countries. Unfortunately, this advantage may be undermined if third countries, as is their right, decide to revoke visa-free access to citizens originating from countries offering CBI programmes, due to national security concerns. For example, Canada imposed visa requirements for citizens from St. Kitts & Nevis in 2014 and from Antigua & Barbuda in 2017 over similar concerns. Both countries have subsequently made changes to their programmes, but their citizens have not yet regained visa-free access to Canada.

The US Government has also repeatedly flagged Caribbean CBI programmes as possibly being used for financial crime, including in its International Narcotics Control Strategy Report 2017. With the current US administration taking an even tougher stance on national security, US scrutiny of Caribbean CBI programmes is likely to continue or even intensify.

The European Commission has already sounded the alarm about the potential security risks that golden passport programmes operated by its own members could pose to the bloc. It reiterated this in its recently released report on those programmes operated in the EU. But this scrutiny is not limited to EU CBI/RBI programmes. In a recently released report, global NGOs, Transparency International and Global Witness, also recently called on the EU to review its visa waiver schemes with those Caribbean countries operating CBI programmes.

In light of this scrutiny, other CARICOM Member States which do not operate programmes have feared that they themselves may suffer reputational and security risks due to the CBI programmes of other Member States. The CARICOM Secretariat has been examining the issue of CBI programmes operated by member states, but there appears to be no public information on what have been the outcomes of this examination thus far.

The other risk comes from increased global competition. The list of countries offering some kind of CBI or RBI programme has grown exponentially in the years since the global economic and financial crisis. For instance, this year Moldova started its own CBI. Moreover, while St. Vincent & the Grenadines is currently the only independent member of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) to not offer a CBI programme due to the current government’s philosophical opposition to these programmes, the leader of St. Vincent & the Grenadines’ opposition party recently reaffirmed his support for launching a CBI programme there. What this shows is that countries around the world still see the economic potential of these programmes and it also means that competition is increasing.

Caribbean countries’ CBI programmes have ranked high on the Professional Wealth Management (PWM) Index. Regrettably, the increased competition between Caribbean CBI programmes both inter se and with other CBI programmes internationally has led to an apparent ‘race to the bottom’ among Caribbean CBI programmes in the form of price competition.

The OECD Challenge to CBI/RBI programmes

In early 2018, the OECD announced that it was examining CBI/RBI programmes as part of its Common Reporting Standard (CRS) loophole strategy and requested public input into the misuse of these programmes and effective ways of preventing abuse. The CRS is an information standard approved by the OECD Council in 2014 for the automatic exchange of tax information among tax authorities of countries which are signatories. CRS jurisdictions are required to obtain certain financial account information of their tax residents from their financial institutions and automatically share this information with other CRS jurisdictions on an annual basis. Most Caribbean IFCs are early adopters of the CRS.

While noting that CBI/RBI programmes may have legitimate uses, the OECD stated that CBI/RBI programmes are a risk to the CRS because they can be misused by persons to hide their assets offshore and because the documentation (such as ID cards) obtained through these programmes could be used to misrepresent an individual’s jurisdiction of tax residence. This, the OECD noted, could occur when persons fail to report all the jurisdictions in which they are resident for tax purposes.

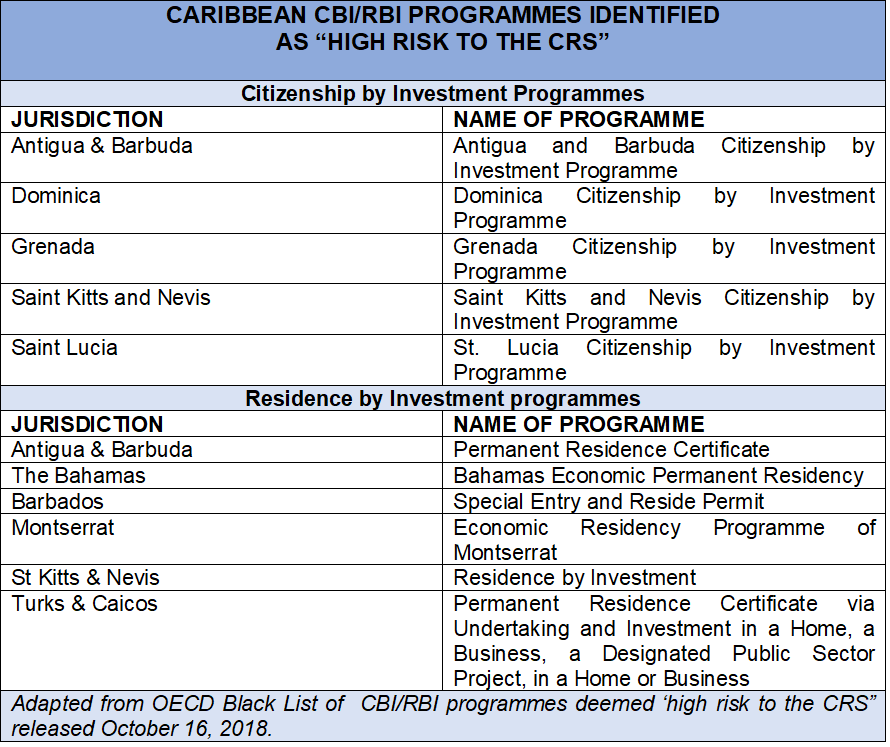

In April 2018, the OECD published a compilation of the responses it had received, which also included responses by countries in the Caribbean offering CBI programmes. In its list of ‘high risk CBI/RBI” programmes to the integrity of the CRS” published in October 2018, the OECD focused on those CBI/RBI programmes which gave access to a lower personal income tax rate on offshore financial assets and those which did not require an individual to spend a significant amount of time in the host jurisdiction.

It should be noted that reporting for CRS purposes is based on tax residence and that just because an investor has obtained citizenship of a country under a CBI programme, does not mean that he or she is automatically deemed to be a tax resident of the country. For example, a person may obtain St Lucian citizenship under St. Lucia’s CBI programme pursuant to the Citizenship by Investment Act and regulations, but under the St. Lucia Income Tax Act, he or she is only deemed to be resident for income tax purposes in St. Lucia for a given income year if he/she has been physically present there for not less than 183 days in that income year.

While the OECD has clarified that the list of ‘high risk CBI/RBI programmes’ was not a blacklist, there is concern about what reputational impact this list may have on the countries whose programmes were named. Financial institutions have been told by the OECD to bear in mind its analysis of high-risk CBI/RBI schemes when performing their CRS due diligence, which potentially brings increased scrutiny for Caribbean countries, which are already suffering the loss of correspondent banking relationships due to de-risking practices by risk-averse global banks.

Have CBI programmes run their course?

Given the growing array of challenges outlined, have CBI programmes run their course? While I do not think Caribbean CBI programmes have run their course, I think that there needs to be strong consideration by each of the countries concerned, and their citizens, of whether the economic benefits justify the increasing reputational and security risks, and to consider what further changes could be made to make their programmes more sustainable.

Caribbean countries are well aware that it is not in their interest for their CBI/RBI programmes to be perceived as loopholes for tax evasion or other criminal activity. It is, therefore, in their interest to work with the OECD to address the concerns raised about the potential for misuse of their CBI programmes.

According to the communique released at the 66th Meeting of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) Authority, that organisation’s highest body, it was noted as follows:

“The Heads engaged in extensive discussions on the matter, noting the unreasonableness of the OECD position, and resolved to undertake comprehensive reviews of the respective CBI and RBI Programmes to ensure that areas where they may be limitations are identified and strengthened.”

This is a promising development and it is hoped that these reviews will be conducted in a timely manner, that the results will be made public in the spirit of transparency and that the recommendations made will be implemented.

To their credit, there already exists cooperation among the Citizenship by Investment Units or equivalents of the Caribbean CIP countries through the Association of the Citizenship By Investment (CIPA). They have also been receiving the assistance of the Joint Regional Control Centre arm of the CARICOM Implementation Agency for Crime and Security (IMPACS).

There is the real risk that countries may become overly dependent on CBI programme revenues for their fiscal and macroeconomic stability during boom times, leaving them vulnerable during periods of leaner revenue inflows. Since 2010, revenues from its programme have buoyed St. Kitts & Nevis’ economy, but the IMF in its Article IV Report of 2017 warned that “ the recent slowdown in CBI-related inflows and the ending of the five-year holding period for CBI properties call for close monitoring of the implications for the financial sector through the real estate market and banks’ exposure to real-estate-related activities.”

On a broader note, a comprehensive study of the economic contribution these CBI programmes have made and are making to the economies and societies of these Caribbean countries is recommended. This would provide empirical evidence of whether the macroeconomic benefits outweigh the reputational and national security risks. In this regard, the recent EU study on its own programmes could provide a good model for CARICOM or the OECS in terms of analysing the state of play and the impacts of Caribbean countries’ CBI/RBI programmes and making recommendations for mitigating the risks identified.

Such a study will require sound data. This brings me to another problem with these programmes – the transparency deficit, which was also highlighted by Transparency International and Global Witness in their report. Obtaining data on these programmes remains regrettably difficult due to the unfortunate reluctance by some authorities to share data publicly, even with researchers. Though some data on the macroeconomic contribution of these programmes may be obtained from those countries’ IMF Article IV reports, other data, such as employment generated by these programmes, are not.

Making data on these programmes publicly available will not only negate the perceived opacity of these programmes’ operation, but facilitate evidence-based planning, monitoring and evaluation of these programmes.

Alicia Nicholls, B.Sc., M.Sc., LL.B., is an international trade and development consultant with a keen interest in sustainable development, international law and trade. You can also read more of her commentaries and follow her on Twitter @LicyLaw.

You must be logged in to post a comment.