CARICOM Secretariat | Turkeyen, Greater Georgetown, Guyana | Thursday, 29 January 2026: A senior Caribbean Community (CARICOM) official has positioned deeper regional integration as a strategic response to an increasingly fragmented and uncertain global trade environment, as global rules-based systems weaken and economic nationalism intensifies.

Ambassador Wayne McCook, Assistant Secretary-General, CARICOM Single Market and Trade, was a panelist discussing Prospects for International Trade in 2026 in the Context of the Changing Global Geopolitical and Economic Landscape – Impact on Trade and the Challenges and Opportunities for the Caribbean and Latin America. The discussion was held on Wednesday, 28 January, at the World Trade Centre in Georgetown, Guyana.

Contextualising the Region’s position, Amb. McCook said: “For our Region, the scars of the immediate past are visible. The devastating passage of Hurricane Melissa encapsulated the dual challenge we face: the existential threat of climate change and the inherent economic vulnerabilities of our CARICOM Member States. Simultaneously, we have navigated dramatic shifts in global trade, driven largely by an intensified “America First” trade policy that has significantly impacted our exports, value chains and supply chains through a suite of unprecedented tariff measures.”

Against the background of what he described as “a truly tumultuous 2025” for international and regional trade, Amb. McCook highlighted CARICOM’s “oneness” and its resilience to navigate the “choppy waters” of the 21st century.

Amb. McCook warned that the erosion of multilateral trade norms is no longer theoretical, but already affecting investment, supply chains, and growth prospects worldwide.

According to UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD), global foreign direct investment fell by 11 per cent in 2024, marking a second consecutive year of decline, with further weakness expected in 2026. Global trade growth has slowed dramatically, falling below one per cent in 2025, even as uncertainty and geopolitical rivalry reshape supply chains.

Despite these headwinds, CARICOM’s trade performance has shown resilience. Between 2023 and 2024, CARICOM exports grew by 32 per cent to US$34.7B, with exports to the United States increasing by 86 per cent. However, recent data reveals uneven impacts across Member States.

The Assistant Secretary-General pointed to the recent steps toward full free movement of people by Barbados, Belize, Dominica, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines as tangible progress toward a more integrated Community.

“Fundamentally, CARICOM integration should be seen as a strategic response to a shifting global order,” he emphasised.

Addressing prospects for international trade in 2026, he advanced a multi-pronged strategy focused on strengthening intra-regional trade, strengthening existing relationships while diversifying global partnerships beyond traditional allies, and deepening economic integration. Central to this approach is the CARICOM Industrial Policy and Strategy (CIPS), and the 25×25+5 food security agenda aimed at reducing food import dependence and boosting regional production.

Read his presentation here: https://caricom.org/deeper-caricom-integration-key-to-navigating-fractured-global-trade-order-amb-wayne-mccook/

Blog

-

Deeper CARICOM integration key to navigating fractured global trade order – CARICOM ASG

-

Is CARICOM Complicit in the United States and Trinidad’s Unlawful Partnership?

Rahym R. Augustin-Joseph (Mr.) – Guest contributor

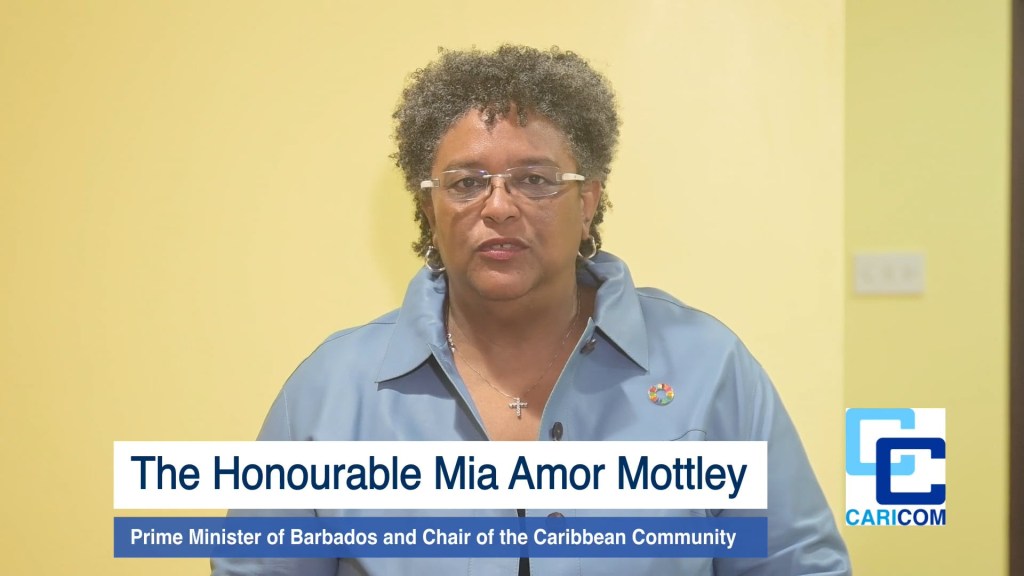

Rahym R. Augustin-Joseph CARICOM countries must always be lauded for their international advocacy at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) among other global forums, as the “conscience of the world” as aptly put by Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley of Barbados, on Geopolitical Issues, Climate Change, Reformation of the International Economic and Political Architecture, AI regulation, Threats to Democracy, Reversal of Modern forms of Imperialism and Neo-colonialism, et cetera.

But they must also be bemoaned for their cognitive dissonance and inertia. Most CARICOM Countries in the recent week, when discussing the recent actions by the United States of America in the destruction of the Venezuelan “drug cartel” vessels in the Caribbean Sea, contrary to International Law and in flagrant disregard for the sovereignty of the Caribbean Region, and consequent permanent stationing in the Caribbean Sea to respond to crime and violence, skilfully omitted the explicit acceptance and endorsement of the above mentioned by our own sister island, Trinidad and Tobago.

It is as if the United States of America on their own, without explicit endorsement determined this security position.

Most countries who discussed the issue only sought to dedicate two lines in their speech to the issue and sought to lay the blame solely at the feet of the United States of America.

It is as if the Caribbean Leaders have forgotten that Imperialism always has benevolent friends, aiders and supporters, who mask their support for imperialism in domestic interests and particularly national security, at the expense of others who are a stone’s throw away. Moreover, they utilise the victimised electorate (whom they have not consulted) and are affected by crime and violence as their justification, for ‘action’ contrary to the rule of law, international diplomacy, peace and established democratic principles.

Obviously, it is impolite, and certainly not diplomatic courtesy for the CARICOM member States to drop our dirty laundry in public, appear fragmented, and bemoan actions of others within the CARICOM grouping at a public forum. This is certainly not the central thesis of this Article.

It is certainly prudent for us to settle our internal diplomatic and political differences (and defend the guardrails of regional integration internally).

But, in the absence of any notable action on the latter, as evidenced through the radio silence of the hierarchy of the Secretariat, Chairman of CARICOM- Hon. Andrew Holness of Jamaica, Institutions of CARICOM et cetera, it raises cause for some concern as to whether the former or the latter is being undertaken.

Should the states have also addressed the issue in a fulsome manner at the UNGA, or should they also be addressing it internally?

However, I am more concerned, with the lack of dialogue, conversation and action internally within the Community to address actions by Trinidad and Tobago that are not in concordance with the objectives, principles, spirit, and positions of the regional grouping as a whole. I interrogate the extent to which CARICOM as an institution can rein in a member who possibly violates the Community principles. And if they are unable to, due to the constrains of functional cooperation, which permits sovereignty of foreign policy, what tools can the regional grouping equip itself with in order to respond to these instances?

Dismissing Some Myths

Now, this is not to suggest nor propose that there is any requirement on any state in CARICOM to sing at the same tone, pace, and volume on every international issue, as the RTC provides not for a ‘unified singular foreign policy’, but ‘coordination on foreign policy’ as noted in Article 6 (h) of the RTC.

So, the Prime Minister is accurate when she suggested that it is her ‘sovereign’ right of her country to articulate their foreign policy position. But, where I disagree is that the unilateral position of Trinidad and Tobago, is certainly at odds with the core pillars of the regional integration movement i.e., foreign policy coordination, as this policy does not contemplate nor advance any type of common ground, deliberative or consultative approach within the region on the resolution to the issue through the utilisation of the American military to supposedly reduce the infiltration of overseas drug cartels which affect Trinidad and Tobago and the wider Caribbean.

Moreover, it is certainly at odds with the long held customary principle within the Region that the Caribbean Sea must always be a zone of peace.

Even as a practical matter, Trinidad actually manages and earns money from the airspace for the Southern Caribbean and is the repository of all flight information for every craft flying in and through the space. As such, their obligations are both essential to our safety and evidence-based posture as a zone of peace.

But the reclaiming of this “lost ideal of a zone of peace” as evidenced by massive murder rates, interregional gang networks and organised crime, as noted by Hon. Kamla Persaud Bissessar from Trinidad and Tobago in her recent UNGA Address, is certainly not going to be achieved through the stationing and utilisation of American Military.

It may see short term results, as evidenced in the ‘neutralisation of supposed threats’ of Venezuela, but the ends may not be successful overtime as this measure is unsustainable, an avenue for retaliatory measures by other countries which can affect the lives and livelihoods of the Caribbean peoples, and a victim of the fleeting geopolitics of the four-year term of the US Presidency. It is also not directly responsive to the research which suggest that a huge percentage of illicit trafficking of firearms and drugs which cause crime and violence originate in the USA, by virtue of their liberal Constitutional gun laws. It is akin to a thief assisting you to look for the stolen goods elsewhere, knowing that they possess it.

But, additionally, it does not deal adequately with the guns and drugs already present within the country, which can be utilised for continuous crime and violence. Nor does it engage in the development and utilisation of technology to track and destroy transnational criminal networks, that do not utilise the ‘sea’ or originate from Venezuela as their route of access to the Caribbean.

But it also does not respond to the local economic and social disenfranchisement among people which fuel crime and violence. Certainly, the USA and Trinidad and Tobago cannot execute ‘all criminals’, in order to respond to crime. As such, other measures must be contemplated and utilised. Those that are in conjunction with the rule of law, international law and other rules-based systems.

It means that overtime the crisis will not dissipate.

Moreover, the literalistic text- which is the cushion upon which these decisions sit does not confines foreign policy in the hands of the individual governors but should always be analysed and assessed in the context of the unspoken conventions and practices from our own individual countries and the CARICOM. As such, the coordination of foreign policy within the Community, is always optimised when countries within CARICOM are singing from the same page of the hymnal, because as I noted in another Op-Ed, history has shown us that “greater results emanate from the Caribbean speaking as one voice within the global political ecosystem, by virtue of their bargaining power as a bloc which eclipses our size constraints. Thus, the utilisation of polar opposition positions within the Caribbean, encourages a colonial ‘divide and conquer’ strategy for developed countries which only elevates their position and agenda, at the expense of the interests of the Caribbean.”

Certainly, one must remember, even at the most basic example, when in December 2011, the government of Trinidad and Tobago was forced to change the venue of the CARICOM-Cuba summit from the Trinidad Hilton Conference Center to the National Academy for the Performing Arts (NAPA). The reason for the change of location offered was that even though the government of Trinidad and Tobago owns the Hilton Hotel plant, the U.S.-owned Hilton Company manages it. Delegates to the conference were all expected to stay at the Hilton Hotel; however, the presence of Cuban president Raul Castro posed a problem for the hotel. This is in contradistinction to other parts of the world where this was tried by the United States and the respective companies and governments protested the actions, on the basis that engaging in the decision of the USA would be enabling discrimination on the grounds of nationality.

Instead, if the interests of the Caribbean were at the forefront of the mindset of these partners or actors- there would be an engagement of CARICOM as a bloc, through a deliberative, consultative and transparent process in order to arrive at a regional agreement on mechanisms and methods to respond to overseas drug cartels infiltrating the Caribbean.

As such, one is only reminded of the many instances of Caribbean disunity propagated by the USA, such as the Ship Riders Agreement in the 1990’s, debates over permitting the US invasion of Grenada, inability to support one candidate in the Commonwealth SG Race of 2022, recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, Venezuela- USA Debacle under President Trump, among others. What is generally done, is the major powers co-opt CARICOM States to be against each other or pick them off one by one through inducements such as aid, financial and technical aid et cetera.”

One of the best examples of the abovementioned philosophy in practice is not only the statement of Kissinger, that “America has no friends or enemies, just interests”, but instead the remarks by Abrams- who held foreign policy positions during the Raegan and George Bush administrations, when commenting on the Ship Riders Agreement after the objections raised by Jamaica and Barbados noted that: But the anti-colonial mind-set, and the insistence on full independence, that marked the 1960s should be relegated to the past. Development in the world economy, and indeed, international criminal activity, have made full independence tantamount to full vulnerability for the smallest states. Far more valuable would be a relationship with the United States that helped guarantee prosperity, security, and liberty.”

But, even beyond that, she identified the underlying ethos of the United States foreign policy when she noted later on that, “ostensibly the Shipriders Agreement is an integral part of the strategy for restructuring American hegemony within global capitalism, national states and sovereignty.”

But, even beyond the legal and historical examples, there is an unspoken convention in the Caribbean that we will always advance the causes that are based on a core set of pillars that have been denied from our peoples for a long time through enslavement i.e., human rights, democracy, the rule of law, people-centred development, and an advancement of resolving the inherent vulnerabilities of small states in the world.

Dr. the Hon. Kenny D. Anthony, as a former leader within CARICOM words must he remembered when he said that “we [must] see our democracy as the main defence against recolonisation. Without it, we would have no choice but to bow to the dictates of global economic forces, which are neither accountable to our populations nor constrained by popular intervention and choice.”

But this unspoken conventions, which CARICOM must protect, even if it means bemoaning or intervening when one of their members acts at odds with it, is buttressed by the fact that all the “CARICOM countries have committed their countries to the Charter of Civil Society, which is a firm statement of the determination to uphold human rights and the pursuit of good governance. As part of this process, there is also an agreement to establish National Monitoring Committees to ensure compliance to the principles of the Charter.”

As such, the actions of Trinidad and Tobago may be contrary to the non-binding Charter of Civil Society i.e., the permitting and encouraging the destruction of vessels and summary executions of peoples in the Caribbean Sea on the suspicion of drugs and crime without criminal due process and respect for human rights.

This is particularly relevant in circumstances where Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago, as Lead for Security in the Quasi Cabinet of CARICOM, has noted in effect at her UNGA Address that, forceful and aggressive action must be taken in order to respond to the evil drug cartels, and because they believe affected nations will always unreservedly resort to morals and ethics and human rights considerations which they blatantly flout and disregard. We will thus fight fire with fire “within the law” because they do not adhere to these values.

This is not only problematic and dangerous language because it defies the domestic, regional and international conventions and laws that Trinidad and Tobago have signed unto.

But the tacking on, almost grudgingly and forgetfully “within the law”, at the end of the statement of fire, is certainly not occurring presently because of the breaches of various conventions and treaties. As a matter of fact, it would be interesting to ascertain what “the law” provides in these instances, and whether there are any legal safeguards for the military intrusion, which are being followed?

But it is dangerous and problematic because it positions war and military interventions as the solution to crime and violence, ignoring the potential innocent death toll and destruction of war as evidenced in history, the length of war without results, and the inability of Trinidad and Tobago to make a definitive statement on the Caribbean Sea and by extension the Caribbean region, without consultation with other CARICOM members. Trinidad and Tobago cannot willingly invite war to the Caribbean, with significant implications for other countries based on geography and a possible spin-off for immigration et cetera, without the buy-in from these respective countries.

But it is also dangerous and problematic because it positions fundamental human rights and international law as being conditional on the actions of criminals, such that if they do not respect human rights, we must not in our response.

But, implicit in this argument is a question of the extent to which this thought, if adopted by every political official, and every citizen, who is also armoured with the power of a military, believed and actualises this, whether you would have any peace, people or prosperity in the respective countries. It is akin to the commencement of a dictatorship where the centre will ultimately determine who and what is worthy of life and death.

This is a slippery slope. The words of Martin Niemoller is thus instructive when he reminded us that “First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a socialist. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.”

Applied in our context, it would possibly mean, that they came for ‘criminals’, ‘immigrants’ and then, the list goes on.

Permitting the application of human rights, which everyone should be entitled to, by virtue of their humanity to be subject to the whims and fancies of political officials is dangerous as it does not create clear, accessible, verifiable, and equal treatment of individuals. But, implicit in the statement is also a suggestion that by utilising the law to dismantle gangs in its current form will only render countries “in name, but without substance.” It is as if, there are not formulae which shows us that both the rule of law and suppression of gang violence cannot coexist.

It is as if there is an absence of laws and processes which can be utilised to suppress and destroy gangs in the Caribbean and the wider world, without resorting to an eye for an eye mechanisms. As a matter of fact, it only signals that we are no different from them and have lost any ingenuity required for responding.

But, even beyond the bemoaning and identification of the problematic areas of the foreign policy position of the Government, there must be an interrogation and assessment of some of the tools within the arsenal of CARICOM which should be equipped to respond to these stances by a member state.

For example, implicit in the role of the Chairman of CARICOM is the underlying obligation to provide definitive statements and a position of the Heads of the Community on major issues facing the Caribbean Region. Obviously, this position and particular response by the Heads of Government and wider Caribbean, must be provided after a deliberative, engaging and consultative process, among themselves even outside the limitations of the scheduled meetings of Heads of Government. Certainly, any division among the Heads of Government, marked by differing voices or deafening silence undercuts the foreign policy coordination objective of CARICOM. It also permits a repeat of history where developed countries continue to employ a divide and conquer strategy, pitting the heads against each other at the expense of the Caribbean people’s safety and maintenance of our democratic traditions.

With the ubiquitous nature of technology, the Heads of Government and specifically the Chairman, cannot thus argue that the lack of a statement is because of the inability to have a forum to receive a common position on the abovementioned.

Certainly, the late Ramphal is instructive when he noted that “we have become casual, neglectful, indifferent and undisciplined in sustaining and advancing Caribbean integration: that we have failed to ensure that the West Indies is West Indian and are falling into a state of disunity which by now we should have made unnatural. The process will occasion a slow and gradual descent from which a passing wind may offer occasional respite; but, ineluctably, it will produce an ending.”

However, to date, and particularly prior to the UNGA, and even within the UNGA, the Chairman of CARICOM, Hon. Holness has tiptoed and circumvoluted around the particular issue, while still notably ringfencing the action by the USA when he noted that “Jamaica welcomes cooperation with all partners in this fight, including the interdiction of drug trafficking vessels, provided that such operations are carried out with full respect for international law, human rights, and with the coordination and collaboration of the countries of the region. The Caribbean has created regional security mechanisms, but these efforts alone cannot match the scale of the threat. What we need is a unified front with the same urgency, resources, and coordination the world has applied to terrorism. Only then can we turn the Caribbean and indeed the wider region into a true zone of peace.”

As such, since the Prime Minister was assertive enough to identify that he will only support actions that respect international law, human rights and collaboration. I take this to mean that he could not thus support these interventions by the United States and aided by Trinidad and Tobago.

But, he does not say that!

But one can glean that since these actions are in flagrant disregard for international human rights law and other international treaties that both these states and others in the Caribbean have signed, that they would be condemned by the Chairman and other Heads of Government.

Certainly, it is clearly evident that these strikes are at odds with (i) due process of law that the ‘drug dealers’ require wherein they must be charged, arrested and be prosecuted in accordance with the relevant criminal laws as opposed to being executed summarily in the seas, (ii) the rule of law which also suggest that everyone must have a fair trial, and that states must comply with their international obligations, which do not provide for summary execution of suspected drug dealers, such as the UN Convention on Narcotic Drugs, which suggest that under Article 35 that individuals who are believed to be engaging in illicit trafficking of drugs, shall be liable to adequate punishment particularly by imprisonment and other penalties of deprivation of liberty, provision of reporting mechanisms and procedures to ensure that the interdiction of the parties are being done in accordance with international best practices and standards, or that the principle of no one being above the law such that these states cannot be the judge, jury and executioner without due process, et cetera.

Further, for example the United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, also notes under Article 17, that respective parties must board, search, and take appropriate action if illicit drugs are found on the vessel. It certainly does not contain any provisions which permit the execution of drone strikes on the vessel. Implicit in this convention also is the satisfaction that there are illicit drugs on the vessel, which in accordance with international best practices must be safeguarded for the evidentiary basis for prosecution of the criminals. But this is not occurring as the drone strikes destroy any ‘evidence’ of drugs and fuels constructive cynicism and lack of trust for political officials among peoples who question whether there were any drugs to begin with. Or, whether these drone strikes are only for strategic geopolitical reasons or only done to justify the earlier position of having the US military stationed in the Caribbean Sea.

As I argued in the other piece on this subject, there must be the provision of appropriate safeguards i.e., reporting, ensuring adequate and accurate intelligence is received and communicated to the political officials and the wider Caribbean Community, proper accessible policies and procedures that provide us with some information on the authority to engage in such intervention and the four corners in which it is occurring, and other requisite communication with other geographically closer member states to prevent unforeseen harm and damage. In effect, these safeguards are to ensure that the objective of the mission is met and is also in accordance with International Law, the rules-based order and best practices.

But certainly, there must be the utilisation of the corridors of power to articulate that view or the public platforms in the Commonwealth Caribbean, in a clearer way to permit the citizenry to be aware of the clear position of the Chairman of CARICOM and by extension the CARICOM itself. Moreover, beyond the speeches at the United Nations, the Chair of CARICOM must provide some definitive position and work towards providing and resolving some of the issues that arise from this intervention as I have identified above.

But, what of the purpose of the Bureau established by CARICOM, which is made up of the former, current and future Chairman of CARICOM, as per Article 12 of the RTC.

Albeit its role is textually limited to focusing on the assistance in the implementation of the decisions of CARICOM, in order to cure the malaise of the implementation deficiency disorder, there is an argument to be made that, their role in “providing guidance to the Secretariat on policy issues, or initiating proposals for development and approval by the Ministerial Councils” can be interpreted as an opportunity to ensure interrogating, analysing, and development of solutions to the question of whether the USA should be utilising our seas to intercept alleged Venezuelan drug dealers, without any due process of law and protection of the law.

As a matter of fact, notwithstanding the RTC does not explicitly specify a role for the Bureau in resolution of disputes, the Bureau has provided leadership along with the Secretary General in the past, in for example, seeking cooperation between two member states, Guyana and Suriname, over the disputed Tigri Area.

As such, the bureau’s informal powers can be utilised again to assist in this resolution, and the agency must have the internal conviction and courage to hold members accountable internally for their actions.

But the problem is not only that of the Leadership but inclusive of the Ministerial Councils, such as the Council for Foreign and Community Relations (COFCOR), which is made up of Ministers responsible for Foreign Affairs of Member States, and is responsible for ensuring that there is a coordination and articulation of a clear position on the subject matter. As noted in Article 16, the Council is responsible for establishing “measures to co-ordinate the foreign policies of the Member States of the Community, including proposals for joint representation, and seek to ensure, as far as practicable, the adoption of Community positions on major hemispheric and international issues. Further, “to coordinate, in close consultation with the Member States, Community policy on international issues with the policies of States in the wider Caribbean Region in order to arrive at common positions in relation to Third States, groups of States and relevant inter-governmental organizations.”

As it currently stands the abovementioned has been otiose.

There is also a case to be made for the quietness of Ministerial Councils, such as the Council for National Security and Law Enforcement (CONSLE) which is responsible for “the coordination of the multi-dimensional nature of security and ensuring a safe and stable community.”

More particularly, Article 17(a), provides an impetus to promote the development and implementation of a common regional security strategy to complement the national security strategies in individual member states, and establish and promote measures to eliminate threats to national and regional security, which also include the mobilisation of resources to manage and defuse regional security crises, of which this is certainly included. These among other responsibilities are included in Article 17(a).

But, even as recent as this year where the CARICOM Heads of Government signed in Jamaica, the Montego Bay Declaration for Organised Transnational Crime and Gangs. Yet still, the resolution to the ‘infiltration of drugs from Venezuela to the Caribbean’ is not being enacted through the principles and practical steps that is provided in this Declaration.

It provided that one of the main aims would be to “renew our commitment to strengthening the Region’s response by implementing effective measures to monitor new trends in illicit firearms trafficking, enact robust legislation to include stringent penalties for firearm and gang-related offences, and to strengthen public awareness on the issues relating to the prevention and prosecution of all forms of organised criminal activities.”

But more importantly, it responded in text to one of the burning desires to maintain sovereignty while still responding to these ordeals, through the strengthening of the regional institutional security structures, to include CARICOM Implementation Agency and implementation of programmes such as the Caribbean Basin Security Initiative (CBSI), to effectively enhance collaboration and sharing of information, to disrupt criminal networks, as well as, leverage shared resources to enable law enforcement and support border security efforts.

However, the Chairman and by extension CARICOM, has only paid lip service to this Declaration and have not engaged in the above which can be assistive in responding to the ordeal. Instead, the regional institutional security structures have been ignored and sidelined in favour of military assistance by the United States, with many disastrous trade-offs that has not been debated, distilled, or get consensus, under the aegis of “ensuring that the friends in the Caribbean are safe.”

What should have been pursued is the strengthening of IMPACS, in order to assist in the identification and interception of the illicit trafficking of drugs, in accordance with International Law and other best practices.

And in circumstances where the abovementioned cannot be pursued, the partnering with the US agencies to ensure oversight and that the objectives of the mission are met and the appropriate safeguards are included in the intervention.

For example, is there a regionally produced satellite mapping of the placement and movement of the American Vessels? Are we certain that these vessels are actually ‘striking’ Venezuelan Vessels and peoples carrying illicit drugs and firearms? Have we agreed on some of the rules of engagement that is sensitive to immigrants, women and children, who may be coerced and trafficked along with the drugs? What is the intelligence utilised to determine whether these interceptions do not disastrously affect Caribbean fisherfolk, especially when Vice President of the United States, JD Vance felt the idea of collateral damage of peoples funny, when he noted “I wouldn’t go fishing right now in that area of the world.”

And how do we alleviate and address the fears of ordinary people on the seas and in communities across the region, who may fear that the Indians would not come to their rescue as suggested by the Minister but agonise over the destruction of their communities with retaliatory strikes by any of the respective parties? Certainly, it is not as tranquil as Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago suggested that it is only those who are criminal masterminds who should be afraid.

All of these could have been components of a collaborated effort between IMPACS and other agencies. Or even alternatively, a new deal could have encompassed equipping IMPACS with these competencies to address the abovementioned, in accordance with International Law.

However, this willing transferring of sovereignty to the USA, is certainly reflective of what Lamming describes as “the staggering nature of the region to resolve the contradiction of being at once independent and neocolonial, and the struggling of new definitions of itself to abandon the protection of being a frontier created by nature, a logistical basin serving some imperial necessity and struggling to move away from being a regional platform for alien enterprise to the status of being a region for itself, with the sovereign right to define its own reality and order its own priorities.”

The abovementioned concerns are those of ordinary peoples across the Caribbean, which must be addressed by their leadership across the Caribbean, even while they fear local gangs and crime and violence.

But the RTC under Chapter 9: Dispute Settlement, does however also provide some recourse for CARICOM Member States to rein in the actions of the Government of Trinidad and Tobago, which may contravene the objectives of the Community or prejudice the object and purpose of the Treaty, required by Article 187(a).

As such, should any CARICOM country feel compelled to act, they could utilise good offices, mediation, consultations, conciliation, arbitration and adjudication as their modes of dispute settlement as noted by Article 188 of the RTC, cognisant that should any of the methods prove unsuccessful, they can easily resort to another mode to arrive at a resolution.

Under good offices, the member states could easily engage the Secretary General of CARICOM or a third party, as required by Article 191. Should they consider mediation as the better mode, they can also agree on a mediator or request one from the Secretary General who will appoint one from the list within CARICOM as noted in Article 196.

Moreover, a member state can also request consultations, where they assert or allege that the actions taken by the other member state constitutes a breach of obligations arising from or under the provisions of the Treaty. After which, they must comply with all of the procedural requirements for consultations established in the Treaty.

Should the Member States assert that these mechanisms are insufficient, they can also resort to the more formal mechanisms of arbitration or conciliation, which establishes commissions and tribunals for adjudication, and provides for an empanelling a list of arbitrators or conciliators, and permits third party intervention, reports, evidence, expert advice et cetera. Recognising the significance of the issue, member states may be tempted to engage in this mode but must be cognisant of the ability of this mode to potentially fracture the inter-Caribbean dialogue and unity because of its ability to become acrimonious and combative. Notwithstanding the above, some member states have still demonstrated diplomatic maturity and Community comradery, even when they have brought each other before the CCJ to adjudicate on matters arising from the Treaty. This option pursuant to Article 211 of the RTC though is also always available to the member states on this matter, should they be able to conjure an argument of a violation of a treaty provision as opposed to the lofty ideals of ‘objectives’ and ‘principles.’ It not only provides that the CCJ has compulsory and exclusive jurisdiction regarding the interpretation of the Treaty, between member states who are parties to the agreement, but also provides the court with the ability to issue an Advisory Opinion, concerning the interpretation and application of the Treaty should a member state request it.

However, one should be more amenable to one of the earlier modes of dispute settlement at the commencement of this process as opposed to the latter.

CARICOM’s silence in the face of Trinidad and Tobago’s endorsement of U.S. military intervention in the Caribbean Sea exposes a deeper crisis of coherence, conviction, and courage within the regional movement. For decades, our leaders have spoken boldly on the global stage yet hesitated to confront contradictions at home invoking sovereignty when convenient and overlooking its erosion when politically expedient. This selective diplomacy undermines both the credibility and moral authority of the Caribbean voice in international affairs. If CARICOM is to remain the “conscience of the world,” it must also have the courage to be the conscience of itself: defending international law, sovereignty, and the Caribbean Sea as a genuine “zone of peace,” not a theatre for external militarisation disguised as partnership.

The instruments for accountability already exist from the Caribbean Court of Justice to the dispute-settlement provisions of the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas but they remain dormant without political will. What the moment demands is not procedural caution but principled leadership: the willingness to speak truth to power, even within our own ranks. To remain silent is to invite the gradual erosion of the West Indian spirit that once defined our integration. If the region cannot summon unity in defence of peace, law, and dignity, it risks becoming not a community of nations but a collection of states, sovereign only in name and subdued by convenience.

Rahym Augustin-Joseph is the 2025 Commonwealth Caribbean Rhodes Scholar. He is a recent political science graduate from the UWI Cave Hill Campus and an aspiring attorney-at-law. He can be reached via rahymrjoseph9@ gmail.com and you can read more from him here.

Image credit: Pixabay

-

Trinidad’s Troubling Invitation of War to Caribbean Shores

Rahym R. Augustin-Joseph (Mr.) (Guest contributor)

Early last week, the Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago, Hon. Kamla Persad-Bissessar, indicated via Press Release, that, her government unequivocally supported the deployment of American Military assets into the Caribbean Region in order to destroy the terrorist drug cartels.

Interestingly enough, the Prime Minister noted that it was not the government’s intention to engage CARICOM, as the foreign policy of each CARICOM state is within their sovereign domain and must be articulated for and by themselves. After all, one’s foreign policy is indeed based on one’s national interests, values, pragmatism, ideology, et cetera.

Albeit, accurate in theory, but not truly in praxis, particularly when a country is within a regional integration movement and history has shown that greater results emanate from the Caribbean speaking as one voice within the global political ecosystem, by virtue of their bargaining power as a bloc which eclipses our size constraints. In fact, some naysayers will argue that when the foreign policy dictates of a country is not solely influenced internally, it is reflective of a reduction in sovereignty. But sovereignty is also an action which permits the island’s foreign policy to be in sync with other countries.

Thus, the utilisation of polar opposition positions within the Caribbean, encourages a colonial ‘divide and conquer’ strategy for developed countries which only elevates their position and agenda, at the expense of the interests of the Caribbean.

Of course, there has been many instances of Caribbean disunity propagated by the USA, such as the Ship Riders Agreement in the 1990’s, debates over permitting the US invasion of Grenada, inability to support one candidate in the Commonwealth SG Race of 2022, recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, Venezuela- USA Debacle under President Trump, among others.

What is generally done, is the major powers co-opt CARICOM States to be against each other or pick them off one by one through inducements such as aid, financial and technical aid et cetera. It is for this reason I support the Golding Commission’s Report Recommendation 26 which suggested “a review of the procedures for foreign policy consultation and coordination in order to avoid as far as possible, the types of conflict and embarrassing positions that have emerged from time to time among CARICOM members depriving it of the collective force it is capable of exerting.”

While the Prime Minister is accurate that CARICOM countries, reserve the sovereign authority to articulate their individual foreign policy position, it is a known fact that her unilateral position undermines one of the core pillars of the regional integration movement, i.e., foreign policy coordination, as noted in Article 6 (h) of the RTC which notes in part that one of the Community’s objectives is “enhanced co-ordination of Member states’ foreign and foreign economic policies.” It is where countries within the Caribbean Community, seek to find common ground on our individual national positions on these myriad of hemispheric and international issues of great importance to the Caribbean Community, such as the Venezuela- Guyana Dispute and the infiltration of overseas drug cartels which affect Trinidad and Tobago and the wider Caribbean.

But what is also ironic and confusing about the Prime Minister’s position, is that she, without the concurrence of her CARICOM colleagues endorsed the American deployment in the ‘Caribbean Region’, not only in the waters close to Trinidad and Tobago, but the Caribbean, while quickly denouncing her Government’s intention to engage CARICOM on the subject matter.

But, even beyond this foreign policy vernacular, Trinidad and Tobago should not make decisions under the guise of the sovereign name of Trinidad and Tobago when these decisions have life and death implications for the wider Caribbean Region peoples without consulting CARICOM.

Thus, the invitation of war to the shores of the Caribbean, with wanton disregard for the potential effects on human life, through the permitting of US military operations which can have counter-military responses within the small landmass in the Caribbean region potentially affecting multiple Caribbean countries is a decision that should not be taken as fiat by one Caribbean country.

As one online commentator noted, decisions about war are not akin to putting on the call of duty video game, but requires careful deliberation, analysis, consultation, respect for international law et cetera.

It is as if the Prime Minister, in the absence of the Chair of CARICOM is speaking for the region without their concurrence, while still attempting to confine her foreign policy position to Trinidad and Tobago.

But, the articulation of such position should have been even more circumspect, because under the Quasi-Cabinet of CARICOM, Prime Minister Bissessar is the Lead for Security (Drugs and Illicit Arms). As such, when she speaks and takes definitive positions, both for Trinidad and Tobago and implicitly for the Caribbean, it is as akin to a response from the CARICOM, which makes it even more problematic, questionable and worrying. After all, CARICOM is one of the bastions of Caribbean sovereignty.

As such, if the regional Quasi Cabinet works anything like our domestic cabinet, Prime Minister Bissessar has just articulated a policy position of CARICOM, while admitting ‘boldfacely’ that she would not be consulting with her CARICOM colleagues.

But one would believe though that such a request for the deployment of military assets has already been made to the Government of Trinidad and Tobago, which prompted this press release. But, instead, the Prime Minister indicated that, no requests have ever been made by the American government for their military assets to access Trinidad and Tobago territory for any military action against the Venezuelan regime.

But, still, she offers it, citing that should the Maduro regime launch any attack against the Guyanese people, her government will provide the access if required to defend the people of Guyana against Venezuela.

What is also concerning about this policy position by Bissessar is that at the domestic level, it is a confining and narrowing of liberal democracy to the political elite, such that the people of Trinidad and Tobago have not been given any meaningful opportunity to form any opinion on whether they are supportive of the utilisation of foreign military assets by the USA, to fight drug cartels and/ or, as a launching pad for war against the Venezuela regime, with significant potential for retaliatory measures against Trinidad and Tobago which will affect their peoples.

Certainly, Bissessar has shown that the people of Trinidad and Tobago, at the recent ballot box, engaged in what Jean Jacques Rosseau calls a simultaneous exercise in, and surrender of sovereignty, such that the very moment they made the x, was the same moment they surrendered their sovereignty to her, such that all decisions of national importance are only decided by the political elite. They remain excluded from engaging in the political lives of their society and have surrendering all of their power to their representatives.

Of, course the common retort of her colleagues and supporters would be that ‘the people voted for a promise of the reduction of crime and violence’ and provided the government with the latitude to engage in measures such as this to pursue the outcome.

A typical example of the ‘ends justify the means’ only that in governance the means, more than ‘the ends’ matter. How and why, you do what you do matters in politics.

But this position is also at odds with other positions taken in Trinidad and Tobago, in the past under Dr. Eric Williams, where in response to internal turmoil with the Black Power Movement, the USA entered the territorial waters; in order to quell the uprising and they were not welcomed by the Government.

But the policy position is also bewildering because is the administration providing their support for the ‘stationing of military assets to destroy drug cartels’ which emanate from or do not emanate from Venezuela?

Or is it to provide the Americans with the launching pad for war against Venezuela if they attack Guyana? Or is it both?

Under the latter, such a retaliatory response under collective self-defence as per International Law, can only be invoked where there was indeed an ‘armed attack’, the victim state must have declared itself to be under attack, and must request assistance, and that this assistance should still be necessary and proportionate.

It apparently is both because days later, we then see video footage of American military assets destroying an alleged Venezuelan vessel on the waters which was allegedly carrying drugs. What this confirms is that there seems to possibly be a request by the Americans for deployment, contrary to the Prime Minister’s assertion which was accepted by the Prime Minister. Further, the aim of the deployment is not only to respond to the Venezuelan state against Guyana, but to also respond to drug cartels emanating from the state of Venezuela.

In any instance, both are problematic.

Certainly, the former is because, notwithstanding the realities that Trinidad and Tobago faces, wherein the data suggests that there has been an infiltration of violence because of the Venezuelan political and economic crisis, it also places Bissessar in a diplomatic chokehold and at odds with the regional position which also recognises that the influx of unlicenced firearms are due in part to the second amendment right under the USA constitution, to bear arms.

Such that, guns continue to be rampant in our countries, which allegedly also come from the USA without the necessary support from the USA, to revisit their internal background checks and support stronger border control to reduce the influx of firearms.

As noted, in a recent peer-reviewed journal article published in the European Journal of International Security by Dr Yonique Campbell, Professor Anthony Harriott, Dr Felicia Grey and Dr Damion Blake titled “From the ‘war on drugs’ to the ‘war on guns’: South–South cooperation between Mexico and the Caribbean” diagnoses the burgeoning gun violence epidemic permeating the Caribbean is as a result of the illegal trafficking of guns stemming from the illegal trafficking of guns from the US, given that an “estimated 60–90% of guns used in criminal acts in LAC are trafficked from the United States”. Further, the article also notes that some of the necessary pragmatic solutions include a “ban on the sale of military-grade weapons to civilians” and “punitive measures against legitimate carriers that convey illegal weapons across national borders as well as monitoring and performance reviews.”

As noted in an instructive piece assessing this situation through the lens of realism, in International Relations Theory, by Dr. Emmanuel Quashie, lecturer in International Relations, notes and he is quite accurate that, “the Trump administration should also declare a War on the illegal trafficking of guns from the US that is responsible for the bloody violence ravaging our communities and destroying and slaughter of our people as the Prime Minster of Trinidad and Tobago Kamala Persad-Bissessar stated in which she seems to blame the issue solely on “evil traffickers”.

Sidestepping this reality, repeating of the American narrative shared by Vice President Vance which does not apportion responsibility and culpability for the crime and violence in this region equally, and not factoring the American complicity into the policy and diplomatic response and engagement is certainly antithetical to the reduction of crime and violence.

As a matter of fact, it continues to sidestep and pass the difficult task of reduction of crime and violence to the United States of America, ignoring the internal national efforts that Trinidad and Tobago could engage in to reduce crime and violence.

As no amount of warships parked outside of Trinidad can fix the issues of trust in the institutions, corruption of the police force, court backlogs, income inequality, lack of youth opportunities which provide an environment for crime to fester, broken education system which creates tiers of citizens, broken family and community structures, border control which reduces the influx of illegal firearms, et cetera.

After all, crime emerges as the data has shown, not simply out of the existence of drugs and guns i.e., manifest tools of crime and violence. But there is an economic, social and political explanation, which lies in the government’s inability to adequately provide for the majority of citizens. Thus, government inadequacy, which cannot be replaced with warships in seas of foreign vessels, must be blamed and responded to.

It is a short-term knee jerk reaction to appease the West and to remove culpability on the nation-state’s complicit role in festering crime and violence through inaction in a time when long-term sustainable actions are necessary.

But the decision is also at odds with prevailing data from the US itself, which notes that as per academic and departmental research, that 84% of the cocaine seized in the US comes not from Venezuela, as they are not a cocaine producer, but from Colombia.” In fact, the major cartels that pose a threat to the USA according to the U.S. DEA are the Sinaloa Cartel, and the New Generation Cartel from Mexico. As such, Dr. Quashie argues and he may be accurate that this position has less to do with Trinidad’s benevolence and altruistic foreign policy in advancement of Guyana’s self-determination, or alternatively in reduction of violence in Trinidad and Tobago, but in the destabilisation of the Maduro regime which may result in their view in a return of the Oil market for Trinidad and Tobago, which was obliterated with the Petro-Caribe Initiative.

But, the naivety of the Prime Minister, unless this is exactly what it was meant to be, seems to be unaware that regime change only benefits the USA’s self-interest of reduction of communism, socialism and other ‘isms’ and is a continuation of their entrenched doctrines in the Caribbean.

Her support as a friendly host will not result in any benefits for the peoples of Trinidad and Tobago and the wider Caribbean but only be a lesson in the realist nature of geopolitics and the international political economy of war and conflict as noted by Dr. Emmanuel Quashie.

Haile Sellasie words are thus instructive when he lamented the inaction of the League of Nations, during the League of Nations address when his country was defeated by the Italian army of Mussolini, that “today it is us, but tomorrow it will be you.”

Dr. Quashie is also thus also instructive and accurate when he noted that, “thus, the idea that the US military presence in the Caribbean will result in a reduction in illegal guns, drugs and violent crimes is to have a fanciful and superficial understanding of Us foreign policy. Plain and simple, it’s about Venezuela’s oil, because they hold the largest oil reserves in the world and nothing to do with supposed “drug cartels,” or “narco-terrorists” or even the issue of illegal guns that actually comes from the United States and are the main source of the burgeoning gin violence that is ravaging our Caribbean communities.”

But it is important for citizens to not be distracted by the Prime Minister’s utilisation of the trauma of the victims as an excuse for diplomatic prostitution, as she implicitly suggest that it is an all-or-nothing approach. Such, that, if the USA warships are not stationed in the waters, crime and violence cannot be solved.

Scholar Lowenthal is thus accurate then as he is now, when he said that “it is a deceptively attractive policy because it seemed cheap and simple, but it is a dangerously short signed, since it amounted to putting out the fires while doing nothing to remove the flammable material.”

The actualisation of the position was thus seen in the US illegal strike on a boat that the Trump administration claimed were carrying 11 Venezuelan gang members from the Tren De Aragua cartel that was loaded with drugs bound for the US which resulted in the destruction of the vessel and the killing of the individuals. The Prime Minister’s response praising the military operation “that the US Military should kill them all violently” is an affront to the rule of the law, due process, right to a fair hearing, proportionality, among other human rights safeguards enshrined in domestic Constitutional and international human rights treaties.

Certainly, in Trinidad and Tobago and within the USA, these offences are not meted out with ‘death’ ‘vigilante justice’ or an ‘eye for an eye’. There is no legal penalty for drug trafficking which is summary execution without due process, i.e., being arrested, charged, provided with a trial and permit the prosecution to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt. In fact, even in circumstances where guilt is proven, or plead by the perpetrators, the penalty is not death by execution as witnessed over the last few days.

As such, why should this be the policy position on the waters by these states, in flagrant disregard for domestic and international law?

Instead, in these countries, which boast and are rated highly their admiration for the ‘rule of law’ officials could have simply conducted maritime interdiction of the drug shipments utilising their intelligence, and the subsequent processing, charging, prosecuting and sentencing of the individuals without attacking the vessel’s occupants.

In some reports, they have noted that in most instances, those transporting the drugs are not big drug traffickers, but rather very young poor people from the region utilised for the enhancement of the drug trade.

But, in typical Caribbean Prime Minister fashion, anyone who interrogates the policy is somehow an enemy of progress, the state, unpatriotic and not a law-abiding citizen, as opposed to embracing critics who question the rationale, nature, safeguards et cetera of the policy position. And hosting forums, conversations among other forms of public engagement meant to address these concerns and invite people into the confidence of the decision making of the political elite.

Patriotism and active citizenship is certainly not clothed in selling Caribbean sovereignty to the highest bidder, but in being self-reflective and interrogating the societal issues and the responses by the political elite.

But the policy position is also problematic because it lacks the necessary details, which can cause citizens to possibly rally and interrogate the position.

It reeks of an unquestioning endorsement of the Ship Riders Agreement, such that the USA can continue to deploy and operate their coast guard outside their territorial waters, to respond to terrorism and other related activities.

So, it is important to ask:

- What of any benefit is the parking of warships in the Caribbean Sea, and how will it actually seek to reduce crime and violence?

- Under what conditions are they present?

- How can any ordinary fisherfolk be certain that with the mechanisms utilised they too would not be randomly killed by military arsenal from the US, as young black men are killed in America, by killing first and finding out they do not possess any weapons after? After all, there have been many cases where some Jamaican fishermen have been subjected to abusive measures by the US Coast Guards who accused them of drug smuggling, burning their boats, stripped searched, and shackled like slaves as noted by Bekiempis in a 2019 article published on the subject.

- For how long will they remain the Caribbean Sea?

- What are the safeguards in place to ensure that they will only pursue their purpose?

- What have the two states and the Caribbean region agree should not be done during this military deployment, such as killing of children, women, among other ‘rules of war’, or is it summary execution of every boat on the seas?

- What if any are the ramifications if the conditions are breached?

- How does the Caribbean people reconcile the history of the West, of utilising our waters and countries as pawns for their own political agenda, at the expense of our small island interests?

- Does the President truly mean his friends in the Caribbean will not be terrorised by Venezuela, or is that there is an ulterior motivation of staving off communism as has been embedded within the US-Caribbean relations?

- Moreover, as one saw with the recent attack, how can one be assured that the intelligence of the USA and Trinidad and Tobago is accurate such that they are indeed attacking drug cartels, and not just immigrants?

- How can we be assured that the execution of the policy is in response to a genuine threat or merely a response to the critics to show that there is a threat?

- When the Prime Minister noted that “all traffickers” should be killed violently, how will they ensure if they engage in summary execution that the individuals killed are traffickers as opposed to the trafficked?

- And, also, what of the diplomatic courtesies of notification and other forms of engagement with neighbouring states when actions will have regional impacts, or is the Prime Minister still of the insular belief that Trinidad’s actions have no impact elsewhere?

- How does the Prime Minister countenance the potential of a return of the US ships and the possible retaliation by Venezuelan authorities on Trinidad and Tobago and potentially the Caribbean region?

- Has the Prime Minister engaged in any analysis of the international law surrounding the abovementioned and satisfied herself that it is being followed, or is there just a disregard for law and order?

- How does this alter the Caribbean philosophical position of being a zone of peace?

Naturally, the Caribbean people could remember the pretence of the USA, when they claimed they were ‘saving medical students in Grenada’, only to realise that it was an attempt to destabilise and destroy the Revolutionary Government led by Maurice Bishop. Or one only has to remember the USA’s interventions in Dominican Republic, Guyana, among others to maintain their hegemonic status and stave off potential communism in their backyard, i.e., the Caribbean.

But, even today with the onslaught of attacks on Grenada’s ability to retain Cuban medical professionals, under the false pretence of solving human trafficking, only to further isolate Cuba’s medical internationalism, is another apt example of the USA utilising their big stick for their own foreign policy outcomes.

History can repeat itself, only if we are not conscious enough to know it and take corrective action. And even if it does not repeat itself, certainly this is a rhyme.

But, in all of these instances, it is important for the defenders of Caribbean freedom and sovereignty to be conscious of how embedded within the US foreign policy has been the Monroe Doctrine, Big Stick Policy, Platt Amendment, among others which advance the USA first interest, and an assumption of an innate hegemonic status in the Western hemisphere.

Such that, any political squabbles in another state would be interpreted as a hostile act against the USA, that they must respond to. Further, that the region continues to be their backyard, such that any action that is taken, must be in consonant with their underlying interests.

It is in contradistinction to the Barbados foreign policy position, which other CARICOM leaders have supported, and seem to adopt at their own, at Independence by Prime Minister Errol Barrow, when he said that “we should be friends of all, and satellites of none.”

But this position by the Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago is also a satellite position because in the latter, it advocates pre-emptively responding to war, as opposed to advocating for the Caribbean sea to continue to be a zone of peace.

Prime Minister Bissessar could have taken the opportunity instead to play a leading role in the Caribbean Region to enhance dialogue over preparation for war. As done in the previous Arnos Vale Accord, Venezuela and Guyanese parties were brought together for dialogue with the ultimate goal of peace. More particularly, the Summit resulted as you know in a Joint Declaration of Argyle for Dialogue and Peace between Guyana agreeing to: “.. directly or indirectly not threatening or using force against one another in any circumstances, including those consequential to any existing controversies between the two States.” This, of course, is in keeping with international law, particularly the customary rule of Article 2(4) of UN Charter, which “prohibits the threat or use of force and calls on all Members to respect the sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of other States.”They also agreed “that any controversies between the two States will be resolved in accordance with international law, including the Geneva Agreement dated February 17, 1966.

And that the talks have not completely yielded peace, does not provide an impetus for the preparation and support of war.

Or are we so satisfied with being the choir singers of the West that we believe that the more we support the West interest and imperatives, we will be included in the ‘America First’ policy, especially with the endorsement of President Trump, that we are his friends and he will protect us.

The words of Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley of Barbados in one of her first UNGA Speeches in 2019 are instructive and should be followed by other Caribbean leaders when she noted, “The time for dialogue, the time for talk, my friends can never be over in a world that wants peace and prosperity. We do not take sides, but what we know is that you cannot propel war over dialogue.”

Eternal vigilance is truly the price of liberty! Let us advocate that peace and good sense prevails!

Rahym Augustin-Joseph is the 2025 Commonwealth Caribbean Rhodes Scholar. He is a recent political science graduate from the UWI Cave Hill Campus and an aspiring attorney-at-law. He can be reached via rahymrjoseph9@ gmail.com and you can read more from him here.

Photo credit: WordPress AI-generated image

-

From Extractivism to Impact: What I learnt in Zambia

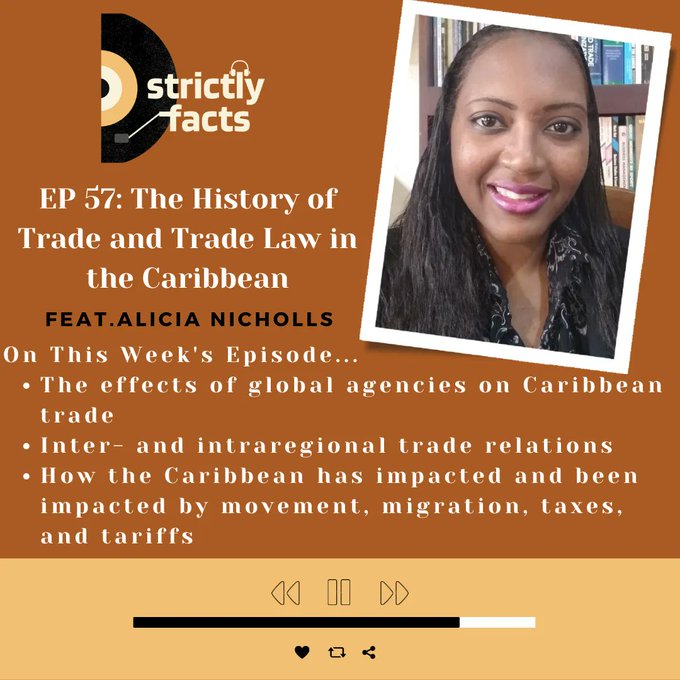

Alicia Nicholls

What good is research if it never reaches the people it is meant to assist? That question echoed in my brain as I boarded the plane from Zambia to South Africa, the first stop on my way back home to Barbados. In the preceding several days, I had been in Lusaka, the capital of the beautiful landlocked African country of Zambia, a country known for its copper exports and being home most notably to the iconic Victoria Falls on its border with Zimbabwe. I had joined fellows from across the Global South for an in-person convening under an inaugural OXFAM Fellowship Programme in which I have been participating for the past few months.

I was deeply grateful for the chance to finally meet the mentors and scholars whose names and faces, until then, I had only seen on a screen during our monthly Zoom meetings. Drawn from across the Global South, we came together in beautiful Zambia not just as bright-eyed early career academics, but as thinkers committed to reshaping the conversations around justice, equity, and the global order.

As a PhD candidate and early-career scholar, I found the experience both inspiring and intellectually-stimulating. Sitting in workshops where our mentors spoke about the role of public intellectuals, I could not help but think of the giants whose work shaped my own worldview—Angela Davis, Cheikh Anta Diop, Walter Rodney, and so many others who never shied away from challenging power in their own scholarship. To be honest, the imposter syndrome was real at times, but so too was the motivation: the reminder that, in my own way, I too could contribute to carrying that torch forward in my research on trade and global financial governance issues.

Over the four days, we engaged in a series of workshops and practical sessions designed to equip us with the tools to move our work beyond the pages of academic journals and to bring it to the communities and struggles that inspired it in the first place. One of the most defining moments for me was an evening dialogue with Zambian community leaders organized by the Fight Inequality Alliance at an Arts Centre which too had its own inspiring origin story. The message from the leaders, a mix of young people and experienced ‘aunties’, was sobering. Too often, academia feels “extractive.” Researchers arrive, collect data from communities, and disappear, leaving behind little of value for the very people whose lived experiences inspired the research. The published research is buried in journals which are often inaccessible behind pay walls.

This struck a chord with me. In academia, our ‘street cred’ comes from publications, particularly in high-impact journals. While important, these are publications that few people outside of academic and policy circles will ever read. Unless that research is then translated into accessible forms such as policy briefs, blog posts, short videos or documentaries, it remains out of reach for the communities who could benefit most. Yet, the incentive structure for promotions and other accolades in academia rarely rewards accessibility or impact of our research. If we are to move from extractive research to impactful scholarship, we must push for an incentive system in our universities that values on-the-ground outcomes as much as journal citations.

As I watched Lusaka disappear beneath the clouds, I reflected deeply on my own journey. Fourteen years ago, fresh out of my Master’s in Trade Policy and about to pursue my Bachelor of Laws, I launched my blog Caribbean Trade Law and Development. My goal was simple. It was to make otherwise esoteric trade issues accessible to everyday readers and to give me a platform through which I could, unfiltered by others, share my thoughts on burning trade issues. Did it give me visibility? Most definitely. Did it help my career as an academic? No, not really. Blog posts do not count toward promotions. Indeed, as I transitioned from the private sector into academia, I had to prioritize traditional academic publishing to “get ahead”, much to the neglect of my blog. Yet, Zambia reminded me that scholarship has a greater purpose when it is accessible. Only then can it move from being extractive to transformative.

I am grateful to OXFAM and to convenor, the Zambian economist, Prof. Grieve Chelwa, for creating this space of reflection, learning, and growth in Lusaka. This fellowship is already reshaping how I think about my role as a scholar, and I look forward with anticipation to what lies ahead.

Alicia D. Nicholls, B.Sc., M.Sc., LL.B. is an international trade specialist and the founder of the Caribbean Trade Law and Development Blog.

Image by Muhammad Syafrani from Pixabay

-

Boosting island economies’ trade through education

Alicia D. Nicholls

From May 27-29, 2025, I had the honour of participating in the Main Summit of the Global Sustainable Islands Summit (GSIS) in my capacity as an academic. Organised by Island Innovation, this third edition of the GSIS was co-hosted with the Government of the Federation of St. Kitts & Nevis. The event welcomed over 200 delegates, mainly from island states and territories from across the Caribbean and world, some coming as far away as the Marshall Islands and Tuvalu!

In this article, I expand on some of the key points I raised as a speaker on the Day 2 panel “Identifying Opportunities to strengthen relationships between global island states”. I focussed on the critical role of education not just as a social good, but an economic asset indispensable for boosting trade both from and between island economies. To this end, I offer at least three interconnected ways in which education can contribute to boosting island economies’ trade: building human resource capacity generally, enhancing trade capacity and serving as a tradeable service.

Building Human Resource Capacity

For many small island economies, their most valuable resource is their human resource endowment. Poor in natural resources, countries like Barbados and Mauritius for example have since their political independence in the 1960s invested significantly in providing universal access to education, a key component of the development success these two countries have enjoyed.

Investments in education not onlyfoment well-being, but also cultivate a well-educated population capable of advancing national development and adapting to global shifts. A well-skilled and educated workforce is vital not just for the local private sector which relies on a robust domestic talent pool, but also as a draw for foreign investors interested in finding the talent they need locally.

As trade becomes increasingly digitised and technology-driven, the education systems of island economies and territories must evolve to nurture citizens who are not just literate and numerate in the traditional sense, but are technologically literate. An educational system responsive to these trends can drive the high-value growth that Caribbean island economies aim to pursue.

Enhancing trade capacity

Education not only contributes to trade competitiveness by building a country’s human resource generally, but also by building its capacity to trade and engage in trade policy making, more specifically.

The University of the West Indies’ Shridath Ramphal Centre’s Masters in International Trade Policy (MITP) programme, now approaching its 23rd cohort, has played a significant and often understated role in developing a cadre of highly skilled trade professionals across the Caribbean region and even beyond these shores. Many of the MITP alumni sit in the highest echelons of governments (including within the cabinet of Barbados), international organisations, donor agencies, business support organisations and private sector firms. Indeed, on the panel on which I spoke at the GSIS 2025, three of the panelists (myself including) were MITP alumnae, and all women.

Understanding trade rules and standards and conducting market intelligence are fundamental for Caribbean businesses to convert the market access they have on paper through the trade agreements and other trading arrangements Caribbean countries have into market presence. Expanding education in areas like sustainability standards, logistics and compliance will ensure the region can fully harness the benefits of trade and regional integration as it seeks to consolidate the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME).

Education as a tradeable service

Education is itself a tradeable service, and one in which Caribbean island economies already participate across the four modes of supply of service defined by the World Trade Organisation (WTO)’s General Agreement on Trade in Servicess (GATS).

Under Mode 1 (Cross-border supply), Caribbean educational institutions increasingly offer online courses, some of which are taken by students abroad, effectively exporting education services. Under Mode 2 (consumption abroad), students from across the Caribbean travel between islands for tertiary education, while foreign students also come to attend offshore medical universities. Under Mode 3 (commercial presence), foreign universities, especially medical schools like Ross University and St. Georges University, have established physical campuses, resulting in a commercial presence/foreign direct investment. Under Mode 4 (temporary movement of natural persons), Caribbean professionals deliver lectures or courses physically on other campuses or other countries, thereby providing educational services physically in another country on a temporary basis.

With certain countries tightening access to their universities for international students, this presents an opportunity for Caribbean universities to strengthen their value proposition not only to serve local students who might have intended to go overseas, but to attract more international students from the Global South and the Global North.

Despite the allure of Global North universities because of their prestigious names and globally recognised faculty, Caribbean universities like The University of the West Indies, already have several advantages: a history of contributing to Caribbean development and well-recognised faculty in many areas, programmes which are tailored to small states’ and developing realities and promoting solutions grounded in our realities, cognisant of our regional history and development concerns, and a well-established track record of research in many areas like climate change, regional integration, development economics and cultural studies. Let us not forget that we are the region which has produced many thought leaders, including one of the world’s foremost development economists – Sir W. Arthur Lewis!

In other words, Caribbean students’ options are not limited to Global North universities and we need a paradigm shift in the thinking that only Global North universities provide good quality education. Many universities here in the Caribbean have educated persons who are excelling at the highest levels in their field, including current and former statesmen, while there are many global South countries which offer scholarships yearly to our nationals to study at their universities. By supporting each others’ universities we would also be contributing to boosting south-south trade in educational services!

Toward Knowledge Economies

To maximise the role of education in trade, it must be embedded within a broader knowledge economy ecosystem. During the summit, I was particularly intrigued by the research shared by colleagues from ODI Resilient and Sustainable Islands Initiative (RESI) on how SIDS can build robust knowledge economies. Their findings underscore the importance of prioritising innovation and the role of education in this. Building these ecosystems requires stronger linkages between universities, governments and industry, greater investment in research, intellectual property rights protection and support for entrepreneurship and start-ups.

Ultimately, the role of education is not merely to promote trade per se. It is to ensure that the trade in which we engage is inclusive and sustainable and redounds to the benefit of our societies. Although it was not identified as one of the 7 pillars of St Kitts & Nevis’ Sustainable Island State Agenda (SISA), education will be key to achieving this road map set out by that government in its commendable quest to become the world’s first sustainable island state.

Final thoughts

If island economies are to boost their trade and promote a future grounded in sustainable growth, inclusion and transformation, education must be a strategic pillar and not an after thought. I am grateful to Island Innovation and the Government of St. Kitts & Nevis for hosting a very engaging and forward-looking summit and for the opportunity afforded to me to contribute to these conversations.

Alicia D. Nicholls, B.Sc., M.Sc., LL.B. is an international trade specialist and the founder of the Caribbean Trade Law and Development Blog.

-

Re-invigorating CARICOM–Canada Trade in a Shifting Global Order

Alicia Nicholls

On May 5, 2025 I had the opportunity and pleasure of being a panelist on the Canada Caribbean Institute (CCI)’s webinar entitled “Canada-CARICOM Relations in the Trump Era”. In this blog post, I share and expand on some of the reflections I made at this session around the theme of reinvigorating CARICOM-Canada trade in this current global dispensation.