Alicia Nicholls

The novel coronavirus virus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has reiterated the need for Caribbean Community (CARICOM) Member States to not only diversify their economies and trading partners, but to deepen intra-regional integration as part of their economic recovery and sustainable development efforts. The astronomical term ‘guide star’ – the star used by a telescope to keep focus on a celestial object as the telescope moves – is a useful reference in seeking to contextualise the promise of a more structured CARICOM-private sector relationship in assisting in the region’s integration, trade and post-COVID-19 recovery.

As recognized by the Addis Ababa Action Agenda on financing for development, the private sector is an important driver of growth, economic activity and job creation and can, therefore, be a valued development partner to governments in the formulation of policies and mobilisation of resources for achieving the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and their 169 targets. To achieve this, the private sector must move from being a mere passive actor which is simply informed of government policy, to a more active actor consulted on and involved in policy dialogue, but not in a way that encourages corruption or rent-seeking behaviour.

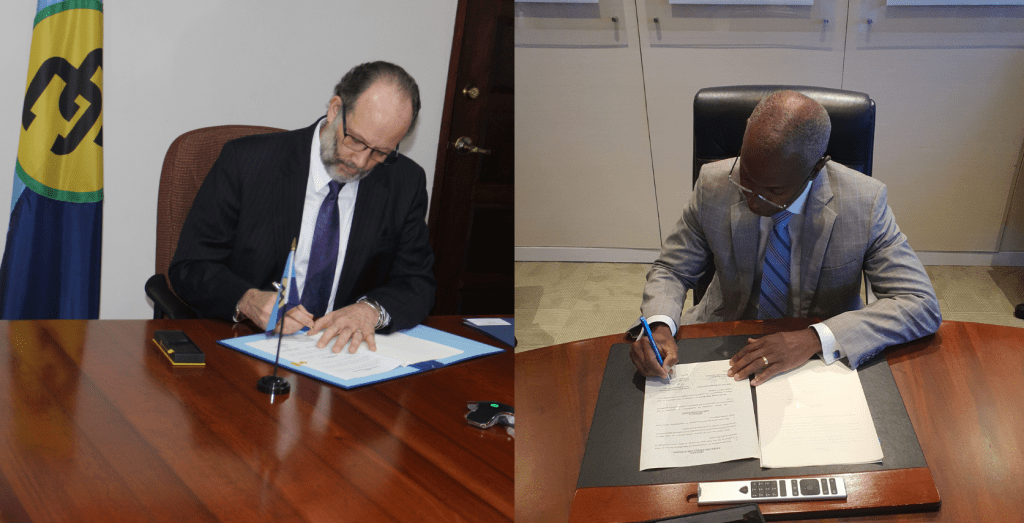

On December 3, 2020, CARICOM took further steps towards a structured relationship with the region’s private sector through the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the recently formed CARICOM Private Sector Organisation (CPSO) for achievement of the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME). This article discusses why these recent developments are both laudatory and encouraging, but that sustainable and inclusive development, and not merely CSME achievement, should be the ‘guide star’ for this relationship if it is to redound to the benefit of the region’s people on a whole.

The new CPSO and the CARICOM-CPSO MOU

Institutionalisation of a CARICOM- private sector relationship has been mooted on previous occasions and more recently, was one of the recommendations (recommendation 31) made in the Report of the Commission to Review Jamaica’s Relations within the CARICOM and CARIFORUM Frameworks (the Golding Report). The most recent ground work for the establishment of a regional body to facilitate more structured engagement between CARICOM and the regional private sector was laid at a meeting of regional private sector officials in June 2019. A year later on June 2, 2020, the CPSO was incorporated as a non-profit in Barbados, where it is presently headquartered.

On October 29, 2020, the CPSO was designated as a CARICOM associate institution, establishing a formal functional relationship with CARICOM. The MOU, whose text is thankfully available on the CARICOM website, establishes a mechanism “for substantive and effective cooperation” between CARICOM and the CPSO in pursuit of a fully implemented CSME. As such, the scope of the parties’ cooperation will be on achieving elements of the CARICOM work programme conducive to the goals of the CSME which seeks to transform CARICOM from a single market to a single economy in which there is free movement of goods, services, skills, capital and the right of establishment.

Without doubt, the private sector’s active involvement is a necessary precondition for the successful implementation and monitoring of the CSME. Under the MOU, the CPSO will have the opportunity to participate in meetings of the Organs of the Community as an Observer and may be invited by CARICOM to participate in Committees, Working Groups and Technical Teams established by the Organs of the Caribbean Community. According to the press release announcing the MOU, the CPSO has already been engaging in several important CSME-related regional discussions.

However, CPSO’s involvement in meetings does not entail a right to vote or to prevent consensus, which likely seeks to ensure that decision-making remains the purview of the government representatives and there is no undue special interest influence on decision-making. The MOU also provides for the appointment of a Joint Technical Team comprising representatives of the CARICOM Secretariat and the CPSO Technical Secretariat, and for working groups to be established for the furtherance of the MOU’s objectives.

Potential benefits of a more structured CARICOM-private sector relationship

There are several potential benefits which this push towards institutionalization of greater private sector engagement could have for enhancing the CSME more specifically, and trade and sustainable development more broadly. While it is governments which negotiate and sign trade agreements, it is firms which must convert this market access on paper into market penetration in practice. The private sector’s knowledge, expertise and experience are important for identifying priorities for CSME implementation, providing feedback on what aspects of the CSME are not working optimally and what barriers they face in regional markets. Additionally, any attempt to flesh out a regional export development strategy, trade policy or industrial policy requires active private sector involvement and engagement in their formulation, implementation and monitoring if these policies are to be effective.

Policy-making at the national and regional level must be sensitive to and account for the diversity within the region’s private sector. The bigger firms of some Member States, such as Trinidad & Tobago, Jamaica and to a lesser extent Barbados, tend to be more experienced in exporting than those of some smaller Member States. It should not just be the larger firms – those whose operations often expand beyond the region – whose views are represented by the CPSO in its dealings with CARICOM organs and bodies. The voice of smaller firms like the micro-firms must also be represented and taken into account. Regional policy making should also appreciate the unique challenges facing women-owned enterprises, such as the difficulty in accessing financing on equal terms as male-owned enterprises, as well as those businesses owned by vulnerable groups, such as the youth and indigenous peoples.

Private sector engagement will also be necessary for informing regional business and investment climate reforms. Despite some noteworthy business climate reforms, especially by Jamaica, ease of doing business remains a problem in many Caribbean countries. Where ranked, no CARICOM Member States ranks within the top fifty countries on World Bank’s Doing Business Index or the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index. Besides improving ease of doing business at the national level, many of the Golding Report’s recommendations, such as the need for greater harmonization of laws and procedures, would also be beneficial for regional firms seeking to expand within the region by improving the predictability, transparency and ease of the regional business and investment environment.

Up-to-date and disaggregated CARICOM-wide trade and FDI data, as well as data on the region’s private sector remains a perennial problem. Private sector firms in the region do not always like to participate in data collection surveys, either because of distrust of what the data will be used for or they fail to see the importance of such exercises, which makes data collection difficult. It is hoped that a structured CARICOM-private sector relationship through the CPSO could lead to better data collection and availability regionally – data which could help inform business decisions and national and regional policy making.

Although the extent of formal CARICOM-CPSO cooperation under the MOU is limited to the CSME, there are other development areas such as public health, climate action, gender equality, finance (including the blacklisting issue) and such like, where more structured private sector involvement in regional discussions could be beneficial. It could be that the framers of the MOU see the CSME as an initial priority, but intend to amend the MOU, as provided for under its amendment clause, to expand the areas of CARICOM-CPSO cooperation at a later date.

If the general public is to trust that this closer CARICOM-private sector relationship will redound to the interest of the public and not special interests, transparency is key. It is therefore regrettable that, despite some improvement, there is still limited detailed information provided to the public on CARICOM meetings held, decisions taken and the status of the implementation by Member States of certain initiatives.

Conclusion

Without doubt, a dynamic, engaged and informed private sector is a necessary condition for expanding Caribbean trade and deepening regional integration with the aim of boosting growth and development. The private sector, which itself has been impacted by COVID-19, will be an invaluable partner in charting the region’s economic recovery post-COVID-19. The CPSO’s creation, its status as an associate institution of CARICOM and the MOU’s signature are promising initiatives for strengthening the institutional mechanisms for private sector consultation in the regional policy making process. That this will lead to regional development is, however, not a fait accompli but a work in progress. It will require commitment by both sides, including trust by the private sector that these initiatives are more than ‘pomp and show’, but that CARICOM Heads of Government see the private sector as a credible partner whose views they will take into account in charting the region’s future development trajectory.

Greater information on the CPSO’s mission, composition and work would be welcomed, including the nature of its relationship and level of cooperation with other region-wide private sector associations such as the Network of Caribbean Chambers of Commerce (CARICHAM), the Caribbean Hotel and Tourism Association (CHTA), the Caribbean Network of Service Coalitions, the Caribbean Poultry Association and the newly formed CARICOM Manufacturers’ Association. Hopefully, these disparate regional private sector organisations will not work in silos but will cooperate and collaborate with each other on areas of mutual interest. If it has not already done so, CPSO should also establish links with cross-regional private sector associations, such as the Caribbean Chamber of Commerce in Europe (CCCE), the Caribbean-ASEAN Council (CAC) and the American Caribbean Chamber of Commerce (ACCC), which can be valuable sources of market information, networks and expertise on current and potential export markets.

It is hoped that this structured CARICOM-CPSO relationship towards CSME achievement will evolve into one of mutual trust and information-sharing between regional governments and the regional private sector in the interest not of a few, but one which places sustainable and inclusive development as its ‘Guide Star’.

Alicia Nicholls, B.Sc., M.Sc., LL.B. is a trade and development consultant with a keen interest in sustainable development, international law and trade. All views herein expressed are her personal views and should not be attributed to any institution with which she may from time to time be affiliated. You can read more of her commentaries and follow her on Twitter @LicyLaw.