Lucius S.J. Doxerie – Guest contributor

The Covid-19 pandemic severely impacted/devasted the economies of countries that have been classified as ‘least developed’ by the international arena. It has prompted me to take a closer look at the ideation of resilience amid global shocks and market failures.

The aim of this brief article is to examine the role of trade in boosting economic growth of least developed countries (LDCs) such as Haiti, Liberia and Timor-Leste. Special attention will be diverted to the type of preferential treatment received and the trade policies needed to increase the growth prospects in a post-Covid period. We first need to highlight the current situation with regard to trade amongst LDC countries as underscored by the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and will posit possible solutions to facilitate an amelioration of trade.

According to (WTO 2022:5) “The top ten LDC exporters represented more than 80 per cent of LDC merchandise exports in 2011; this declined to 73 per cent in 2020. LDC exports continue to be concentrated in five major destination markets: China, the European Union, the United States, India and Thailand.”.

As early as the 1930’s, discussion around the benefits of lessening restrictions to international trade and investment was actively happening among countries. In 1948, an international agreement was established among countries to reduce barriers to trade. After eight rounds of meetings, a General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was formed, and in 1995, the World Trade Ogranisation (WTO) was established. The WTO is an international trade governing body that is tasked with monitoring, enforcing and liberalizing trade amongst countries (Suranovic 2010).

The key reasons why countries trade is summed up below.

- Differences in technology (Ricardian theory of comparative advantage)

- Differences in resource endowments (Pure exchange model of trade and Heckscher-Ohlin factor proportions model)

- Differences in demand (Monopolistic model)

- Existence of economies of scale in production (Increasing returns to scale)

- Existence of government policies among countries

In the reality, trade takes place for many reasons. There is no single model or theory that captures all the reasons. For example, the Ricardian model, which focuses on the differences in technology among countries posits that everyone benefits from trade whereas on the other hand the Heckscher-Ohlin model suggests differences in endowments are the reason for trade and that there will be losers and winners. These traditional trade theories illustrate a myopic justification for trading as countries trade for a myriad of reasons. According to experts like Suranovic, most of these theories of trade are very simplistic in nature and generate unrealistic assumptions.

So let’s now discuss, especially in consideration of the quote below:

“Least developed countries (LDCs) have been recognized by the United Nations since 1971 as the category of the states, which are deemed highly disadvantaged in their development process, for structural, historical and also geographical reasons”(Białowąs and Budzyńska 2022:1).

As early as 1979, least developed countries have been receiving preferential treatment from advanced economies as part of the Tokyo round of the GATT. These preferences fall under what is coined the generalised system of preferences (GSP). As such, they have enjoyed exclusive schemes geared at entry into the markets of advanced economies by removing barriers such as tariffs and quotas from the early 2000s (Klasen et al. 2016).

According to the WTO, “the Istanbul Programme of Action for LDCs (IPoA) for the decade 2011 to 2020 identified trade as one of the eight priority areas of actions for the economic growth and sustainable development of least-developed countries”(WTO 2022:3).

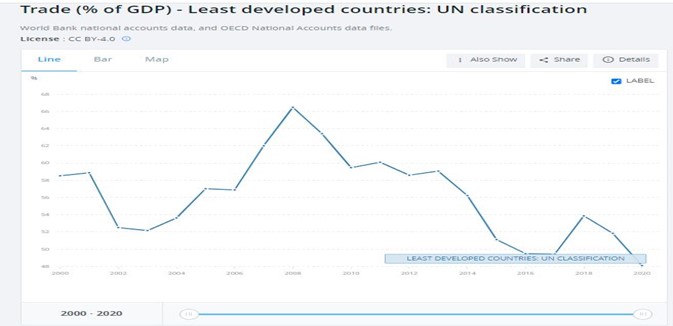

Trade as a percentage of the Gross domestic Product (GDP) for LDC’s since the year 2000 is reflected below in figure 0.1.

The graph above illustrates that trade as a percentage of GDP for LDCs rose steadily from as early as 2003 up until the financial crisis in 2008. A downward pattern continued for another eight years until 2016, then there was improvement. However due to the Cocid-19 pandemic a downward movement has been evidenced since.

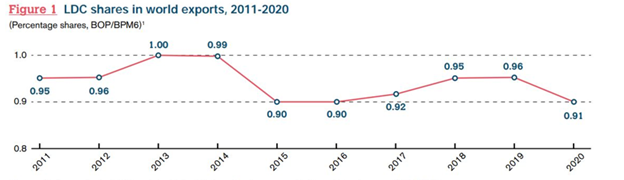

The graph below illustrates the latest statistics of the LDCs share of world exports.

Source (WTO 2022)

We can clearly see that there was steady expansion of exports between 2017-2019. After the pandemic, there was a sharp decline of .04%, falling way below the expected target set by IPoA. (WTO 2022) shows that LDCs have seen declines over the last ten years in merchandise exports in all areas except clothing. Although LDCs received preferential treatment, not all goods and services exported are covered (Antimiani and Cernat 2021).

So what does this all mean, and what’s the bottom line?

There is clear evidence supporting the WTO’s preferential treatment towards increasing the revenues and economic prosperity of LDCs (Antimiani and Cernat 2021). Notably, there is still room for further easing of trade barriers especially due to the shocks created by the pandemic. This is further underpinned by larger regional trade blocks emerging amongst developed countries undermining the efforts of the WTO (Palit 2015). A 2016 paper carried out by (Klasen et al. 2016:5) using econometric techniques highlighted that “only Canada’s, Australia’s and EU’s trade preference systems have a positive and significant impact on LDCs’ exports”. Therefore, the following recommendations are proffered in the interest of economic uptake and growth through trade for LDCs.

- Establish regional trade agreements among LDCs to help increase their market share.

- Provide concessions for value added goods from LDCs within the global value chain for finished products exported by WTO members

- Increase the unilateral agreements enjoyed by LDCs especially duty and quota free access to world markets on a wider range of products

- Increase the production and institutional capacity of LDCs by providing technical support to their industries

- Improve the LDC service waiver allowing it to cover more areas within the service industries

These recommendations will allow LDCs to improve their trade practices, have more standardized procedures, facilate growth of local sectors which, in turn will increase the overall welfare of the economy and the people post covid.

Note: Multiple WTO reports, textbooks and journals from industry experts were utilized in the writing of this article.

Lucius S.J. Doxerie is an aspiring economist and co-founder and CEO of Stratagem Paradigms Inc. He is a Chevening Scholar currently enrolled at the University of Bradford completing a Master of Science in Economics and Finance for Development.

REFERENCES

Antimiani, A. and Cernat, L. (2021) Untapping the full development potential of trade along global supply chains: ‘gvcs for ldcs’ proposal. Journal of world trade 55 (5), 697-714.

Białowąs, T. and Budzyńska, A. (2022) The Importance of Global Value Chains in Developing Countries’ Agricultural Trade Development. Sustainability 14 (3), 1389.

Klasen, S., Martínez-Zarzoso, I., Nowak-Lehmann, F. and Bruckner, N. (2016) Trade preferences for least developed countries. Are they effective? Preliminary Econometric Evidence. Policy Review 4.

Palit, A. (2015) Mega-RTAs and LDCs: Trade is not for the poor. Geoforum 58, 23-26.

Suranovic, S. (2010) International trade: Theory and policy. The Saylor Foundation.

WTO (2022) Boosting Trade Opportunities for Least Developed Countries. WTO. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/boottradeopp22_e.htm Accessed 22/03/22.

You must be logged in to post a comment.