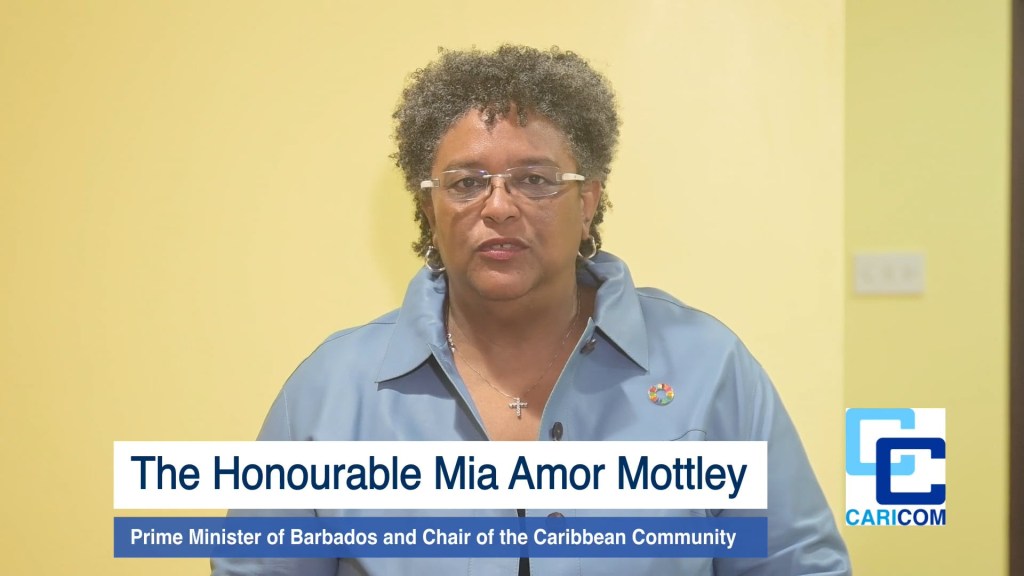

(CARICOM Secretariat, Turkeyen, Greater Georgetown, Guyana – Friday, 4 April 2025) –

The transcript of the Statement from the Honourable Mia Amor Mottley, Chair of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) on the impact of the global crises on the Caribbean.

I speak to all our Caribbean brothers and sisters today, not as the Prime Minister of Barbados, but in my capacity as Chair of the Caribbean Community.

Our world is in crisis. I will not sugarcoat it. These are among the most challenging of times for our region since the majority of our members gained their independence. Indeed, it is the most difficult period our world has faced since the end of World War II, 80 years ago. Our planet faces a climate catastrophe that worsens every year. We have a cost-of-living crisis that has been bedevilling us since the disruption of supply chains, when the COVID-19 Pandemic triggered the shutdown of the majority of countries.

Misinformation, disinformation and manipulation are relevant. The mental health crisis is causing hopelessness among many of our young people, and regrettably, crime and fear are on the rise. We’re fighting wars in the Holy Land, in Europe and in Africa. Countries are distrustful of countries and neighbours are distrustful of neighbours. The international order, the international system, my friends, is in great danger of collapse, and now we are on the precipice of a global trade war.

Our Caribbean economies are largely reliant on imports. Just go to the supermarket or visit the mall or the hardware shop or the electronic store, and you will see that most of the things there are not produced in this Region. Many of those commodities are either purchased directly from the United States of America or passed through the United States of America on their way to the Caribbean region. That, my friends, is a legacy of our colonial dependence. Together with colleague Heads of State and Heads of Government, we have been working to diversify ourselves away from this dependence.

We’ve already started to reap some successes, especially in the field of agriculture, for example, but we still have a long way to go. As we do this work, we have to be mindful that those recent announcements that have been made in the last few days will impact us very directly as a Region and as a Caribbean people.

We are working and will continue to work to become more self-sufficient, but I want every Caribbean man and every Caribbean woman to hear me. This trade war and the possibility of a US $1 million to $1.5 million levy on all Chinese made ships entering US harbours will mean higher prices for all of us at the corner shop, higher prices at the supermarket, higher prices at the electronic store, higher prices for us at the shop, higher prices for us at the restaurant, higher prices for us at the current dealership and beyond.

A lot of Caribbean people will think that these things that you are seeing on television news or reading about are far away and “They don’t impact on me.” A lot of people think “I’m just a farmer”, “I’m just a schoolteacher”, or “I’m just a mechanic.” They say, “I live in Saint Lucy in Barbados”, or “I live in Portmore in Jamaica”, or Kingstown in St Vincent, or Arima in Trinidad or Basseterre in St Kitts & Nevis, or San Ignacio in Belize.

“These problems are far away from me, and they don’t impact me.” That is what you will hear them say. But the reality, my friends, is that if you buy food, if you buy electronics, if you buy clothes, it will impact you. It will impact each of us.

My brothers and sisters, our Caribbean economies are not very large. So, we are, and have always been, at the whims of global prices. If Europe and China and the U.S. and Canada and Mexico are all putting tariffs on each other, that is going to disrupt supply chains, that is going to raise the cost of producing everything, from the food you eat, to the clothes on your back, to the phone in your pocket, to the car you drive down the road, to the spare parts that you need for critical infrastructure. That means higher prices for all of us to pay, and sadly, yes, this will impact all of us, regardless of what any of our Caribbean governments will do.

We could lower our tariffs to zero in CARICOM, and it will not make a lick of difference, because our economies are small and vulnerable. This crisis, my friends, will impact not only goods, but it may also have a large spillover effect on tourism. We suggest that the region takes steps to sustain the tourism industry as likely worsening conditions and many of our source markets will have negative impacts on people’s ability to travel. We call on our regional private sector and the tourism sector to come together and to work with governments to collaborate for an immediate tourism strategy to ensure that we maintain market share numbers as a region.

My friends, I pray that I’m wrong, and I’m praying that cooler heads prevail across the world, and leaders come together in a new sense of cooperation, to look after the poor and the vulnerable people of this world, and to leave space for the middle classes to chart their lives, to allow businesses to be able to get on with what they do and to trade.

But truly, I do not have confidence that this will happen.

So, what must we do?

First, we must re-engage urgently, directly, and at the highest possible level with our friends in the United States of America. There is an obvious truth which has to be confronted by both sides. That truth is that these small and microstates of the Caribbean do not, in any way or in any sector, enjoy a greater degree of financial benefit in the balance of trade than does the United States. In fact, it is because of our small size, our great vulnerability, our limited manufacturing capacity, our inability to distort trade in any way, that successive United States administrations, included, and most recently, the Reagan administration in the early 1980s went to great lengths to assist us in promoting our abilities to sell in the United States under the Caribbean Basin Initiative. We will see how these tariffs will impact on that. That spirit of cooperation largely enabled security, social stability and economic growth on America’s third border in the Caribbean, or as we have agreed as recently in our meeting with Secretary of State Rubio, what is now our collective neighbourhood.

Secondly, we must not fight among each other for political gain. Because my dear brothers and sisters, as the old adage goes “United, we stand and divided, we fall.”

Thirdly, we must redouble our efforts to invest in Caribbean agricultural production and light manufacturing. The 25 by 2025 initiative, ably led by President Ali, seems too modest a target now, given all that we are confronting. We must grow our own and produce our own as much as possible. We can all make the decision to buy healthy foods at the market instead of processed foods at the supermarket.

Fourthly, we must build our ties with Africa, Central and Latin America, and renew those ties with some of our older partners around the world, in the United Kingdom and Europe, and in Canada. We must not rely solely on one or two markets. We need to be able to sell our Caribbean goods to a wider, more stable global market.

My brothers and sisters, in every global political and economic crisis, there is always an opportunity. If we come together, put any divisions aside, support our small businesses and small producers, we will come out of this stronger.

To our hoteliers, our supermarkets and our people, my message is the same. Buy local and buy regional. I repeat, buy local and buy regional. The products are better, fresher and more competitive in many instances. If we work together and strengthen our own, we can ride through this crisis. We may have to confront issues of logistics and movement of goods, but we can do that too.

To the United States, I say this simply. We are not your enemy. We are your friends. So many people in the Caribbean region have brothers and sisters, aunties, uncles, grandmothers, grandfathers, sons and daughters, God children living up in Miami or Queens or Brooklyn or New Jersey, Connecticut, Virginia, wherever. We welcome your people to our shores and give them the holidays, and for many of them, the experiences of a lifetime.

I say simply to President Trump; our economies are not doing your economy any harm in any way. They are too small to have any negative or distorted impact on your country. So, I ask you to consider your decades-long friendship between your country and ours. And look to the Caribbean, recognizing that the family ties, yes, are strong. Let us talk, I hope, and let us work together to keep prices down for all of our people.

My brothers and sisters, there’s trouble in our Caribbean waters, but the responsibility each and every day for much of what we do and what much of what we grow must be ours, if we take care of each other, if we support each other, if we uplift each other, and if we tap into the strength and innovation of our common Caribbean spirit, we will see this through.

Our forefathers faced tribulations far worse than we will ever do and yes, they came through it.

My friends, my brothers and sisters, we can make it.

We shall make it.

God bless our Caribbean civilization.

Thank you.